The Geometry of Empathy: Spatial Conjectures on Developmental Psychology

June 02, 2025

By Aybars Asci

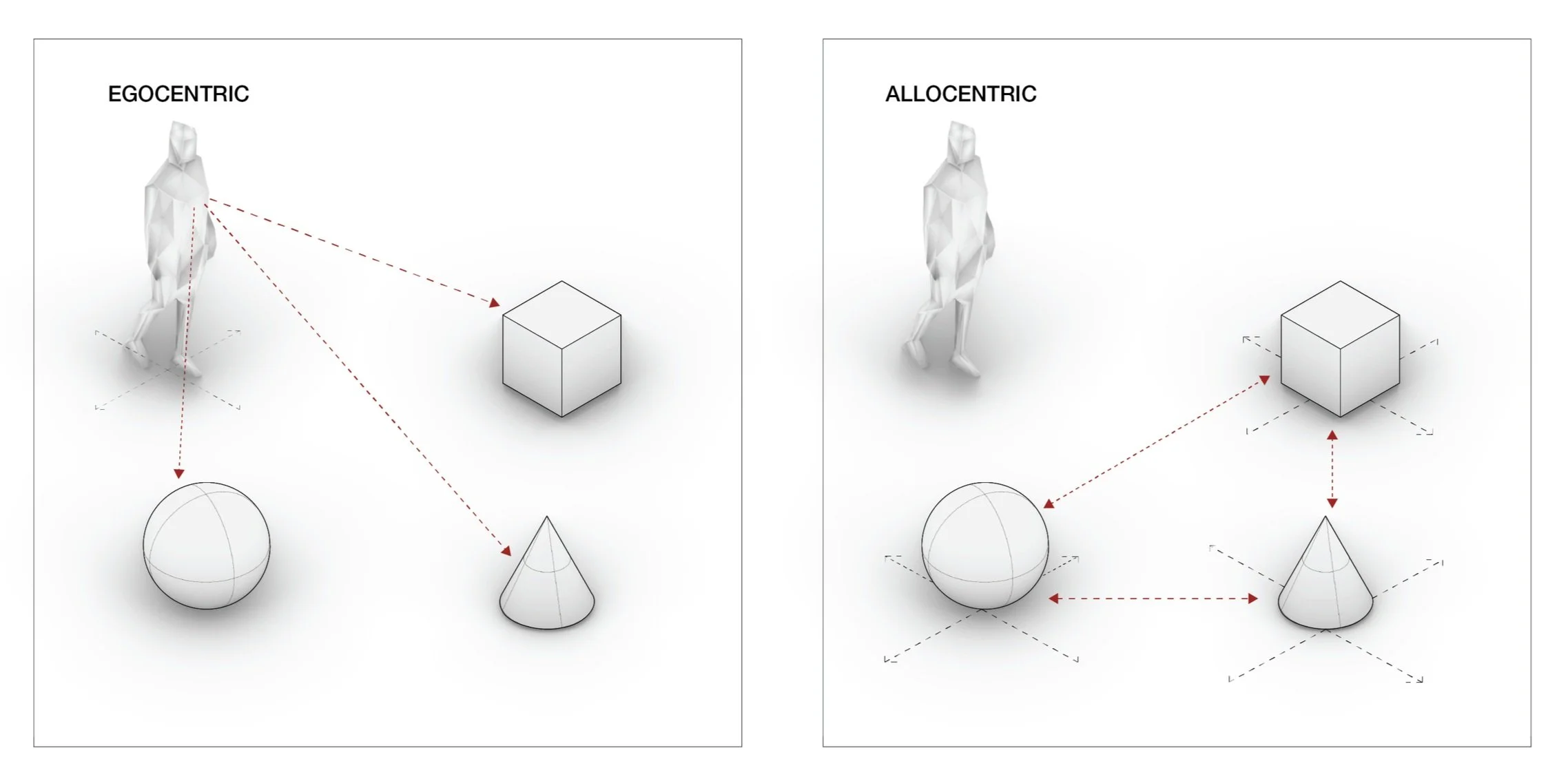

Spatial perspective, the home turf of architects, has also been, as Barbara Tversky points out, a focal point for scholars studying object recognition, environmental cognition, developmental psychology, neuropsychology, and language. (Tversky, 1996) In the study of spatial cognition, the construct of the spatial perspective is defined in relation to a frame of reference that comes either from a viewer-centric (egocentric) or an external (allocentric) position. (Figure 1)

Figure 1 - Spatial Frames of Reference

Spatial frames of reference effectively inform of how we define, navigate, and establish relationships in our environment. We are all born into our egocentric frame of reference. As Michel Denis points out: “Each of us, with his/her own egocentric view of the world, interacts with other people who have their respective egocentric views of a shared environment. The question here is that of our capacity to adopt the perspective of other people." (Denis, 2018, p.65) Taking the perspective of other people does not come naturally to us, and it has a cognitive cost. But it is worth it, because, as Denis argues, “by combining together spatial information taken from different viewpoints, people will enjoy the possibility of forming richer representations of their environments." (Denis, 2018, p. 66)

Since spatial frames of reference define the nature of our perspective taking, and these frames of reference share the common spatial attributes with the physical environment, I suggest that manipulating the construct of these spatial perspectives has the potential to help us shift perspectives. In other words, we can purposefully design “spatial nudges” to ease the cognitive cost toward adopting allocentric frames of reference. The significance of being able to shift our frame of reference goes beyond enriching spatial cognition; it is also how we can create a more empathic environment.

Perceptual Space (P-Space) And Language Space (L-Space)

In the early stages of human development, our awareness of things or people outside ourselves is connected to the world that we can directly experience with our senses. Only the objects or people that are within this perspectival space exist, and when they disappear from that perspectival space, not only do they disappear from perception, but their entire existence seemingly vanishes. Early learning specialists correlate a baby getting upset and crying at a nursery during a parent drop-off with the understanding that for a baby, the disappearance of her parents from her sightline is associated with their loss from her life. Consider this common occurrence: a baby sits in her highchair, and she throws an object, like her toy or spoon, on the floor. She starts crying when the object she just threw away disappeared from her sightline. An adult interferes with this situation and grabs the object from the floor, cleans it, and puts it back on her highchair. The baby smiles at first, and then throws the object back out again. In this scenario, the baby is not testing the parent’s patience, but rather, she is learning something important. She is learning that [this] object in front of her continues to exist even when she throws it on the floor, which is outside of her sightline. The reappearance of the object with the assistance of an adult reassures the baby that the object that she threw away is still there even when she can no longer see it. Piaget calls the realization that something continues to exist—even when it’s no longer sensed—“object permanence.” (Mooney, 2013) Even though the baby cannot talk, she uses gestures of pointing, as she cognitively develops object permanence. Before the acquisition of language, she uses the deictic gestures of being [here] and seeing [this] object.

As children start to talk, how do they acquire deixis in language—pointing with words—when they have encountered it, thus far, only by pointing their fingers? Unlike categorical words like “spoon” or names like “Joe” that do not change depending on who speaks and where they speak from, the correct use of deictic terms is dependent on the speaker’s position and the proximity of the subject matter to the speaker. Deixis is contextual. All forms of deictic words and expressions are dependent on anchoring a point in time, space, and a person—a deictic center.[1] There is foreground and background, there is a vantage point, a perspectival hinge, in deictic words. Deixis is where language enters perspectival space. And this is the space where it shares a common ground with architecture: geometry.

In an essay on how a child acquires English expressions for space and time, psycholinguist Herbert H. Clark argues that the child acquires them “by learning how to apply these expressions to the a priori knowledge [that the child] has about space and time.” (Clark, 1973, p.28) This a priori knowledge comes from a space Clark calls “P-space,” the perceptual space the child is born into. He writes:

The child is born into a flat world with gravity, and he himself is endowed with eyes, ears, an upright posture, and other biological structure. These structures alone lead him to develop a perceptual space, a P-space, with very specific properties. Later on, the child must learn how to apply English spatial terms to this perceptual space, and so the structure of P-space determines in large part what he learns and how he quickly learns it. The notion is that the child cannot apply some term correctly if he does not already have the appropriate concept in his P-space. (Clark, 1973, p.28)

As a baby discovers the phenomena of gravity that forces the objects she throws toward the floor, into disappearance from her vision, she is developing a broader world than her innate P-space, where objects exist beyond her immediate vision (object permanence). The baby expresses herself using deictic expressions in absence of spoken language. As she acquires the language expressions that relate to the concepts of P-space, she enters what Clark calls “L-space,” the concept of space underlying English spatial terms. L-space coincides with P-space, as such that “any property found in L-space should also be found in P-space.” (Clark, 1973, p.28)

Clark summarizes the characteristics of the P-space of a person, in upright position—what he calls the canonical position—as “the optimal position to perceive other objects visually, auditorily, tactually, etc.” (Clark, 1973, p.34) And he defines these in geometric terms: “P-space consists of three reference planes and three associated directions: (1) ground level is a reference plane and upward is positive; (2) the vertical left-to-right plane through the body is another reference plane and forward from the body is positive; and (3) the vertical front-to-back plane is the third reference plane and leftward and rightward are both positive directions.” (Clark, 1973, p.35) (Figure 2)

Figure 2 - P-Space. The diagram is created based on Herbert Clark’s definition.

According to Clark, “the perceptual features in the child’s early cognitive development (his P-space) are reflected directly in the semantics of his language (his L-space).” (Clark, 1973, p.30) The critical role that the P-space plays in the development of the individual’s L-space is an important hinge in the interrelationship between deixis, architecture, and empathy. P-space is innate to the person’s experience; it is phenomenological; and it is directly relatable to the physical environment. Architects shape the P-space, and as such, they have an influence on the development of the L-space for both the individual and society. Therefore, in theory, if we can design the P-space purposefully, we can shift the semantics (meaning) and potentially create a place that catalyzes empathy.

Visual Echo in The Perspectival Space: Personal-Deixis and Empathy

My theory is that spatial deictic words like [here], [there], [this], or [that] and personal deictic words like [I/we], [you], or [he/she/they] can be acquired by children easier in a space that deliberately constructs the deictic depth in the P-space. The construct of the P-space can make proximity and non-proximity explicit and hence the correlation between the language and the space can be made more direct.

In the Avenues Early Learning Center project in Shenzhen, we designed a purposefully choreographed series of niche spaces for the students. (Figure 3) Here, three identical frames are arranged on the same axis, across a space that is open to below. Each frame creates a seating niche, lined with the same green fabric, marking its presence clearly within its respective white wall. The niches look almost identical with small variations. The first one, shown in the foreground, has a keyhole shape and features a writable glass surface that allows for a visual connection to the double-height atrium below. The middle niche also features writable glass, but its shape is square. The third niche, which is the farthest away in Figure 3 and visible only through the middle niche, is open to the student commons located in front of it and has a solid back wall.

Figure 3 - Avenues Shenzhen Early Learning Center three niches conjecture.

All three frames create their own canonical position, but share the same axial arrangement of a single-point perspective. This creates a strong visual connection between each of these individual deictic centers. But the critical element of this design is the visual echo, created by the “three-niches” arrangement. For the children in the foreground, their perspective-taking—based on their own deictic center—is contextualized by the students directly across from them. In the acquisition of personal deictic words like [I] or [we], the impact of the three niches P-space on the cognitive development of the children is to help develop an awareness of the perspective of [others] that co-exist with them in the same perspectival space. Such awareness can catalyze empathy in learning environments. In broader terms, by facilitating the acquisition of language in a specially constructed P-space, we can encourage a shift in the egocentric bias of young children toward a more empathic worldview.

Derived from our design study at Avenues Early Learning Center, the “three niches” conjecture is a P-space construct that assists with the acquisition of deictic expressions with empathy in early childhood. The three niches conjecture is constructed as follows: Define three deictic centers and locate them on the same perspectival axis, the positive and negative directions of each being parallel to the axis. On each deictic center, the vertical front-to-back perpendicular plane of the person is visually framed with an identical or similar marker to achieve a visual echo. The framing elements should have conspicuous geometric, textural, and color similarities.

If the grammatical first person is located on the deictic center at either end of the axis, all the three personas can be subsequently located in the same direction. This type of arrangement for the P-space will result in the construction of second and third person for the L-space, and hence the perspective taking can be expanded to the [other] in the same directional axis. If the grammatical first person is located in the middle, the second person is visible across, whereas the third person will be behind the first person, or toward the negative direction. The first person located in the middle will need to pivot to visually engage with the third person. (Figure 4)

Figure 4 - Three niches conjecture diagrams showing different locations of first person and the relative positioning of the second and third person.

The forced perspective construct of the three niches conjecture creates three egocentric reference frames that align toward the same vanishing point. The visual echo of each frame is intended to catalyze perspective taking for each individual, shifting the focus of spatial cognition to social interaction. In this specially choreographed P-space, which allows multiple perspectives in the same narrative, a shift from an egocentric frame of reference to an allocentric frame of reference is intended.

Visual Counterpoint in The Perspectival Space: Time-Deixis And Empathy

Raphael’s fresco The School of Athens (1509–1511) is located in the Stanze di Raffaello (1508) a series of richly illustrated reception rooms in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican. The School of Athens is famous for its perspectival depth, which, particularly when seen within the context of the room, offers an interesting point of view on time deixis—the fourth dimension of the deictic center’s geometric construct. When we stand straight in front of Raphael’s fresco, we look into a perfectly constructed perspectival space. (Figure 5)

Figure 5 - The School of Athens, Raphael (1509–1511)

In our P-space, the positive time axis represents the front, meaning [tomorrow] is yet to come ahead. And yet, the figures of Aristotle and Plato are walking toward us. The deictic future of the ancient Greek philosophers runs in the geometrically opposite direction from our own deictic future. The visual counterpoint between our perspectival vantage point and that of the philosophers creates a mirroring of time deixis. Embedded within the beauty of his painting, Raphael created a purposeful construct: a portal through time for intellectual empathy.

If we step back from our frontal position in order to get a view of the overall room, we will notice that the arch that carefully frames the fresco also supports the dome of the room we’re standing in. (Figure 6) [Today], inside the fifteenth-century building, as we stand in front of this Renaissance fresco, looking into an ancient Greek scene, we exist in a purposefully constructed P-space where time gains new meaning in our L-space.

Figure 6 - The fresco is located on the east wall of the Stanza della Segnatura, one of the four Raphael Rooms in the Apostolic Palace in the Vatican.

The scene at Stanze di Raffaello and Raphael’s masterful trompe l’oeil offer a valuable design strategy. The visual counterpoint between the perspective of the individual observer and the perspective of the painting, in a setting that has a strong visual echo between the architecture of the room and the architecture depicted in the painting, causes a reciprocity between the time axis of the observer’s deictic center and the philosophers’ deictic centers. It is this reciprocity that allows us to have a deeper understanding of context.

Inverting The Deictic Center, And Empathy Through Awareness

The deictic center locates the first person at the center of the construct, making it an inherently egocentric frame of reference. In both design strategies discussed to counter this egocentric bias—the visual echo and the visual counterpoint—the concept of juxtaposition plays a key role in perspective taking and helps us move toward a deeper understanding of people, time, and space, consequently allowing a more empathic environment. For instance, in the three niches conjecture, the first, second, and third person are juxtaposed on the same deictic axis, encouraging us to see the point of view of the other.

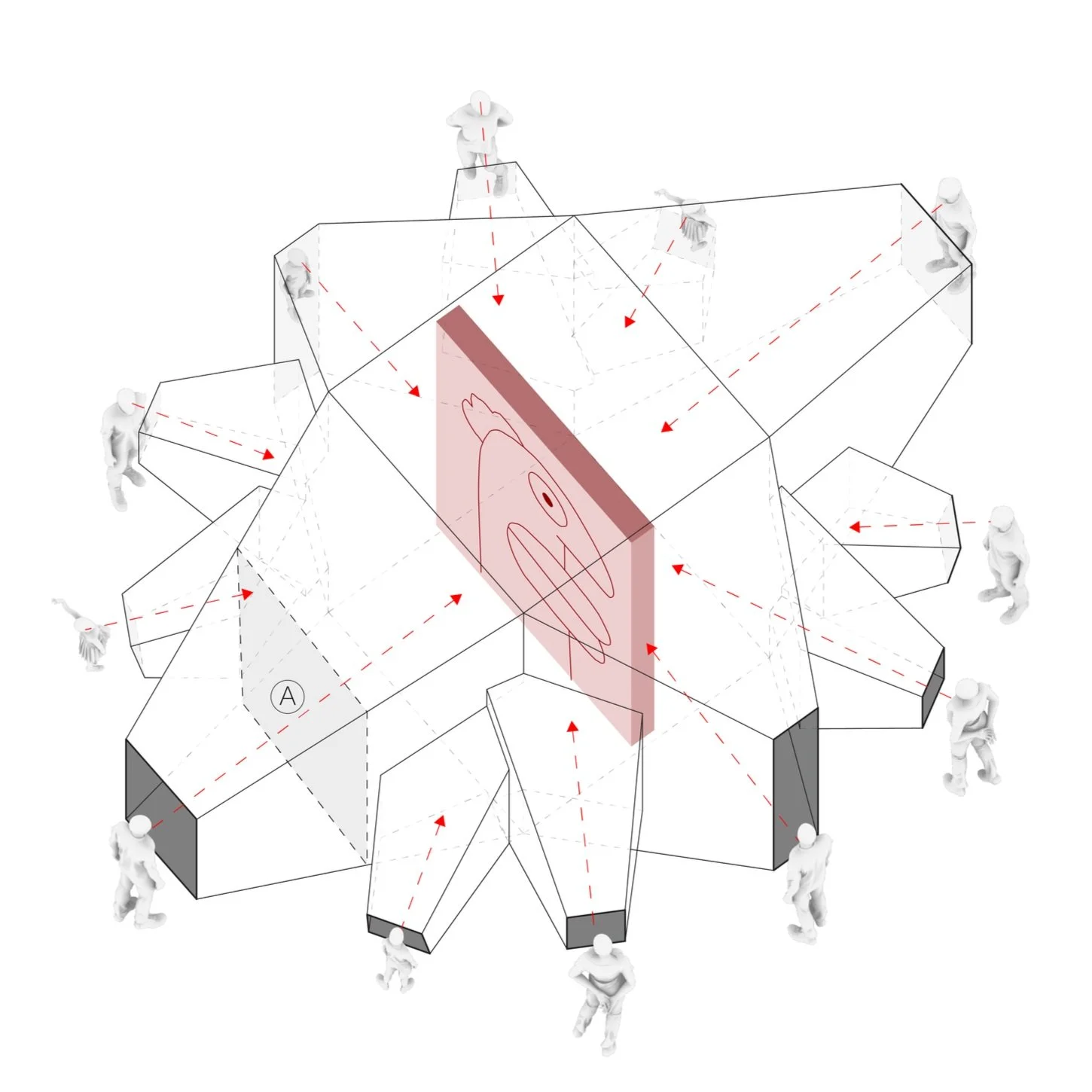

What if we invert the deictic center, and instead of putting the first person at the center of the construct, we put the object at the center, and thus allowing the nonhuman object to construct its own narratives? This conceptual shift will create a third spatial frame of reference, different from the egocentric and allocentric frames of references, both of which are based on human-centric points of view and carry the contextual bias of the time and place in which the narrative is constructed. By contrast, a spatial frame of reference that locates a non-human object as the anchor gives an autonomy to the object, allowing it to construct its own narratives. I call this concept an “isocentric frame of reference.” The object in an isocentric frame of reference has the agency to construct its own deictic center through projections toward the first person’s deictic center. (Figure 7) The potential to construct different juxtapositions within each of these projections will allow us to build multiple narratives for the same object, deepening our understanding of it.

Figure 7 - Comparison of the three spatial frames of reference. Isocentric frame of reference, added to the egocentric and allocentric frames of reference as a new way to conceptualize pluralistic narratives.

The next project creates a device that constructs an isocentric frame of reference for a historical artifact, allowing us to build both emotional and cognitive empathy toward the socio-political circumstances and consequences of the time the object was constructed and, subsequently, subverted. Furthermore, the juxtapositions within the spatial construct allow us to deepen our understanding of ongoing conflicts and their respective consequences to society and the environment.

Kowsky Plaza, located along the Battery Park City Esplanade in New York, is a small pocket park that contains a seemingly circumstantial assemblage of public attractions such as a dog park, a children’s playground, a volleyball court, New York City Police Memorial, and a segment of the Berlin wall. The Berlin Wall segment was given to the Battery Park City Authority in 2004 by the German Consulate, and today sits on the Eastern Edge of the park, uncomfortably close to an apartment building, paradoxically surrounded by a metal picket fence. Most park visitors stroll past it without even recognizing it.

Concerned about the deterioration of the mural on the wall segment due to its decades-long exposure to varying weather conditions, the Battery Park City Authority issued a request for proposals from architects to design a protective envelope in 2022. The pragmatic concern of paint deterioration and the discussions to find solutions for preservation inadvertently brings us into deeper questions of what this object represents, how we should preserve it, what kind of relationship should we have with it and what kind of relationship should it have with us, and notwithstanding, how it should sit at the eastern corner of Kowsky Plaza.

The Berlin Wall, the most recognizable symbol of the Cold War, was, of course, more than a wall; it was a series of walls, fences, a vehicle ditch, traps, observation towers, and a zone ominously named the “death strip,” separating East and West Berlin. The segment of the wall that sits at Kowsky Plaza was originally located along the Kreuzberg neighborhood in Berlin, and the mural on the wall was painted by the French artist Thierry Noir in 1984. Noir’s abstract minimalistic outlines with few colors grew out of the pragmatic realities of finishing the painting quickly without being caught by East German border guards. When Noir started painting the murals, at first, the West Berliners were suspicious; they took it as some sort of propaganda activity, but later embraced the murals. He was joined by other artists. For Noir, this act of defiance was a subversion of a war barrier into a humanistic canvas. As he stated, the act of painting the murals made him stronger than the wall itself. (Noir, n.d.)

But what does his act of defiance, this subversive transformation of a Cold War apparatus into a humanistic artifact mean today, when a piece of it sits at the corner of a pocket park in Manhattan surrounded by a picket fence? In its new context, is it reduced to just a memento, a souvenir brought to New York City from another time and place?

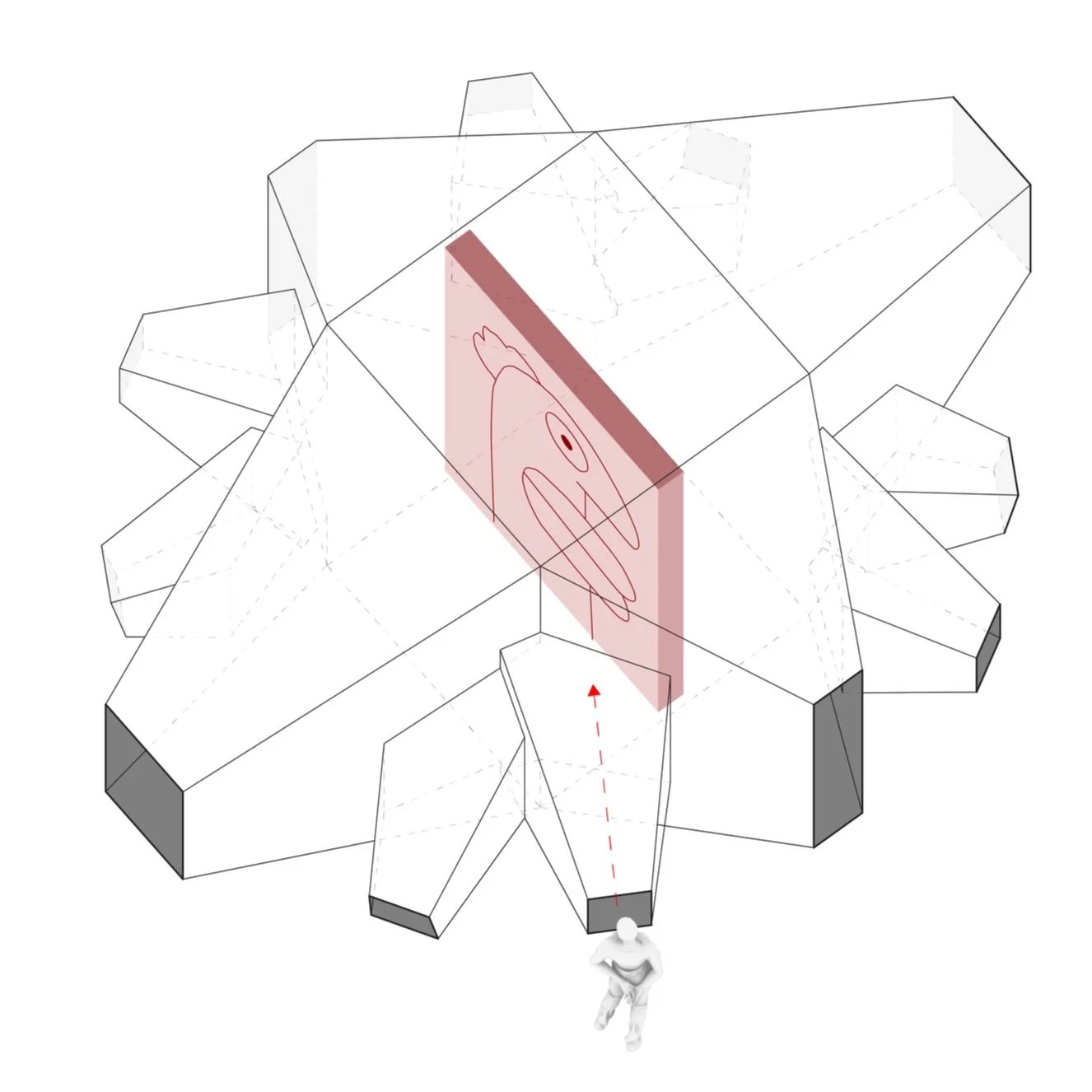

As my office contemplated the Battery Park City Authority’s requirement to create a shelter for this segment of Berlin Wall, we asked ourselves how we can redefine the dual narratives of humanity—oppressive and liberating—represented by the canvas and its painting. How could we reterritorialize this complicated piece of history in its new context and give it a voice that elevates it from an object of consumption as in a souvenir; transforming it into something that can bring us a heightened awareness of socio-political events of past and present? Our design proposal constructs an apparatus that locates the segment of the wall within an isocentric frame of reference. We designed two versions of the same concept. The first one is based on pure radial projections. The other option recognizes the cardinal axes of the wall and introduces the radial projections inserted in between them. (Figure 8) Both are manifestations of the same concept, even though they have different formal expressions.

Figure 8 - Two different schemes of the isocentric frame of reference. The Berlin Wall fragment is located at the center, illustrated with the red rectangle.

In both schemes, the individual deictic centers for each person looking to the wall sees a framed view of the mural. The carefully curated perspectives toward the wall are in fact part of the isocentric projections of the wall, constructing its own narratives. Along each deictic axis, a frame is constructed to juxtapose on other narratives. The new narratives on these frames are intended to be temporary exhibits that will be curated by other artists that reflect their own conceptualization of the wall. (Figure 9, Plane A) In other words, they will be layering over Noir’s painting, creating yet another form of subversion of the wall.

Figure 9 - Plane A shown in the diagram is located at each deictic axis and the juxtaposed stories are placed on these planes.

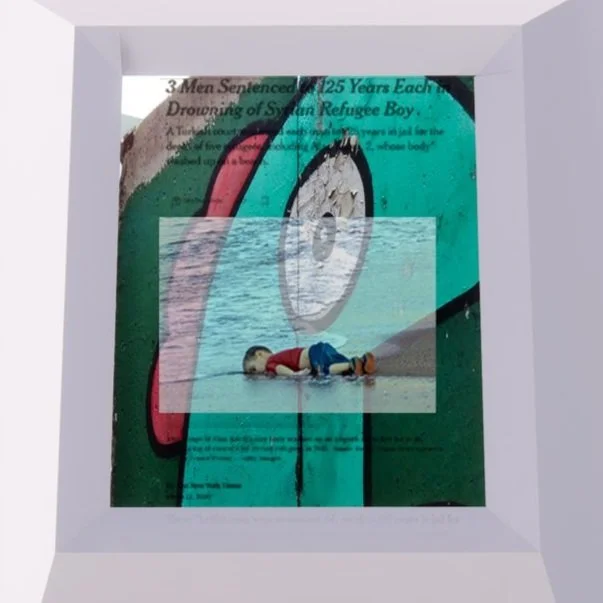

To illustrate how juxtapositions work at the isocentric frame of reference, we have curated one story line. Figure 10 shows one of the perspectives of the wall juxtaposed by the image and story of the Syrian refugees trying to cross the Aegean Sea on makeshift boats in 2015. In this particular image, we see a little boy who tragically drowned and washed out to the beach. The eye of the mural is looking toward us as we look back at it. And there is the little boy, lying motionless on our deictic axis. In this juxtaposition, Noir’s drawing of the big eye is looking at the little boy, witnessing another human tragedy, on another death strip—in this case an Ancient Sea transformed into one.

Figure 9 - Plane A shown in the diagram is located at each deictic axis and the juxtaposed stories are placed on these planes.

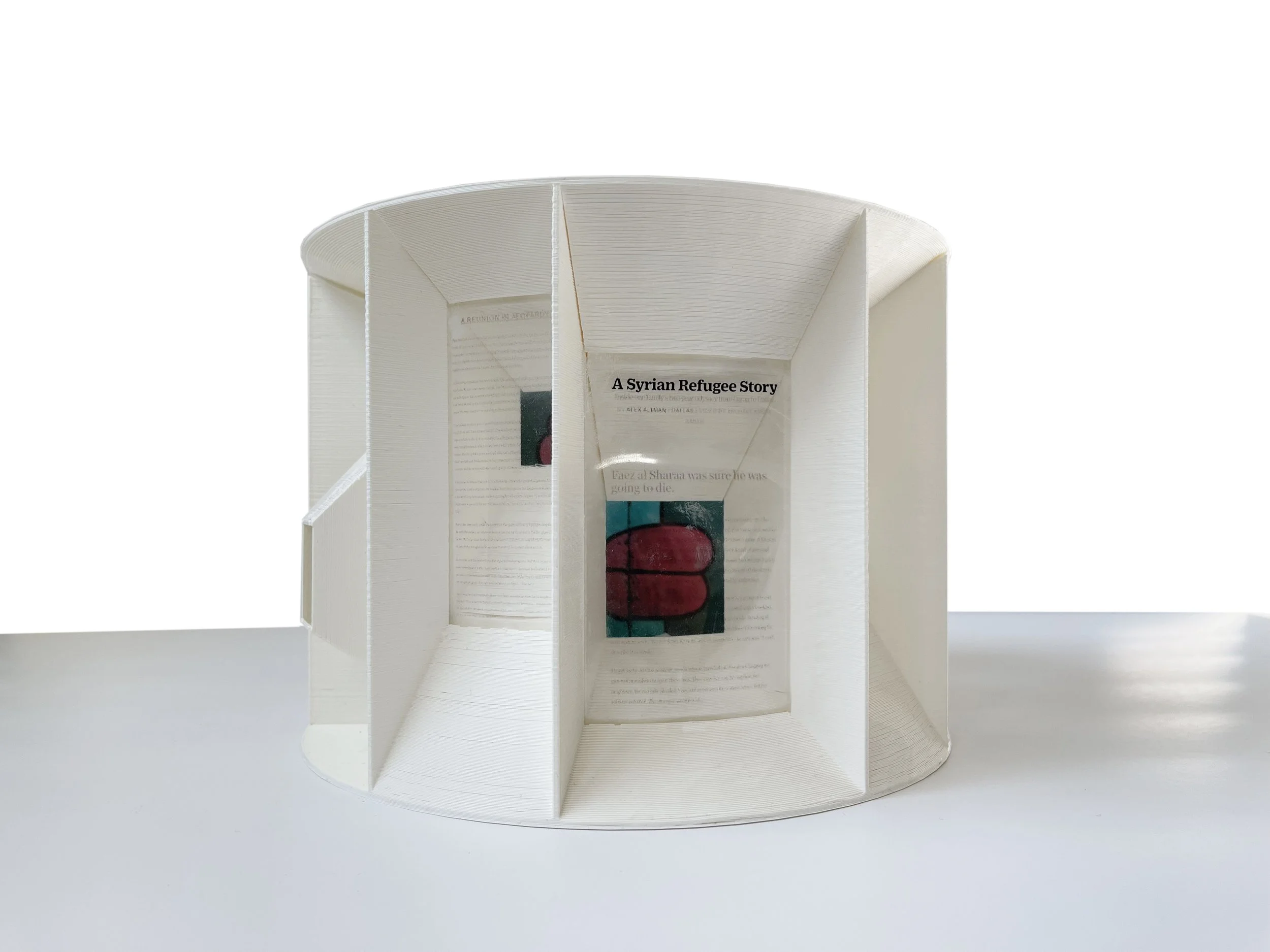

In Figure 11 we can see another juxtaposition: the lips of the mural framed over a news story of the tragedy. In this narrative, the bright red lips are motionless. The person reading this is reminded of the importance of her own voice. The mural reminds us that we have a responsibility to speak up and to act against atrocities. The person looking at these juxtapositions is encouraged to think of this segment of Berlin Wall not as a relic from the past, but as a reminder that human tragedies continue to unfold and peaceful coexistence of societies is contingent on fragile balances. These balances depend on perpetual emotional and cognitive empathy for each other, as much as they depend on international treatises and protocols.

Figure 11 - Photograph of physical model.

Losing The Balance In The P-Space, Cognitive Dissonance And Empathy Through Grief

In Herbert Clark’s definition of P-space, a person stands upright on a ground plane, defined as the reference plane. Gravity is the only force that anchors a person to this reference plane, and it defines the directions of [above] and [below]. Clark’s P-space is conceived to be on terra firma, even though he does not explicitly state it. Imagine defining the P-space at sea on a nautical vessel. The gravity that defines the vertical axis is now coupled by another force: buoyancy. The forces of buoyancy and gravity perfectly align on the same axis only when a ship floats in perfect trim. At this moment of perfect trim, a person standing on the naval vessel will be in a P-space where the horizontal plane acts, in theory, as the ground plane, but it is fundamentally different.

Even in dead flat water, the perfect trim creates a horizontal plane for a person to stand upright only temporarily. Because, unlike the reference plane on terra firma, on a ship the reference plane is a place of constant negotiations between the opposing forces of gravity and buoyancy. As the nautical vessel heels, the axes of gravity and buoyancy shift, and between these two parallel forces, a rotational correction is generated toward balancing the heel. Therefore, a person standing on this vessel experiences two reference planes: one is the physical tilted floor that is defined by the heel, and the second is the horizontal reference plane that is the plane of balance, which exists only temporarily.

The directions of our deictic center are in constant motion, and only on momentous occasions, with the alignment between the forces of gravity and buoyancy, do we catch the moment of perfect balance. Since our a priori understanding of P-space is naturally formed on land, the experience of P-space on a ship, due to the constant swing of the ground plane caused by these coupling forces, requires a translation of our L-space. If, as Clark argues, there is to be a strong relationship between the P-space and L-space, we can hypothesize that, a person who is born on a ship and has never set foot on land, until their complete acquisition of language, will have a much different L-space than a person born and raised on land. This person may develop a different conception of balance than their land born counterpart.

The balance on a ship in some circumstances does not restore itself. The coupling forces between buoyancy and gravity are vectoral, and when they do not counter each other—in other words, when the axis of gravity shifts to form a negative moment arm—the tilt will increase, first gradually, then exponentially, as the moment arm increases, and the ship will eventually sink. The vectoral misalignment can be the slightest of angles that initiates a trajectory of no return, and with that, the reference plane (what we associate with the horizontal ground plane) in our P-space, and hence our understanding of balance, is irrecoverable.

On April 16, 2014, 2.7 kilometers off the coast of Byeongpungdo Island on the southern tip of South Korea, a naval tragedy took place. The MV Sewol ferry made a sharp turn, causing it to list 20 degrees into the water, which in turn caused its cargo to move on one side of the ship, tilting the ship further and effectively losing its restoring force. The shift of the cargo and the heel angle of the ship resulted in a negative righting moment, which initiated an irreversible process. In approximately two and a half hours, the ship sunk, and with it 306 people died. Of the victims, 250 were students from Danwon High School who were on a school trip.

When the MV Sewol made its fatal turn, it initiated the irreversible course of events governed by the rules of hydrostatics. At that moment something else was initiated as well: the P-space inside the ship altered. The upright position of our land born P-space was now stuck on an angle that could not restore itself. When we are in the sea born P-space, we are in a translation mode, like someone in a foreign country who is constantly translating. The meaning of being upright means being in balance, or, as Clark states, in our “canonical position.” Our L-space—which encompasses our understanding of the world—has been defined by this canonical position.

What happens if the balance between the forces of buoyancy and gravity is lost, and the heel does not correct back to the horizontal plane? What does one feel in a P-space of gradual loss of balance? According to social psychologist Leon Festinger, a disequilibrium or a cognitive dissonance is an uncomfortable internal state that we need to resolve. (Festinger, 1957) For instance, when it rains and we don’t get wet, we would be in a state of dissonance, because this condition would be contrary to all our past experiences. (Festinger, 1957, p.14) Likewise, we expect the forces of buoyancy and gravity to continuously balance themselves out in a ship so that we know that we are safe. For our land-based L-space, this means that we can still find our canonical position on a reference plane that mimics the ground even if it does it momentarily between the swings of the coupling forces.

On a ship, a tilt that is not restoring itself is an unfamiliar and scary territory to be in. The impact of the tilt inside the MV Sewol is heard in the emotional video recordings of the students trapped on board. They laughed in the beginning, even joking whether this event might make it to the evening news. They mentioned the Titanic, the infamous naval disaster of modern times. In these online recordings, you could hear them sing the song from the feature movie. But as time passed in their disconcerting condition, they observed the increasing angle of the tilt. They propped themselves on the walls so as not to slide. One student, who was getting increasingly upset looking at the tilt, can be heard saying:

“The ship is 85 degrees tilted, the temperature in my brain 100 degrees.”

“Do you see? The ferry is being sunk. Being sunk…”

Their laughs and jokes gradually turn into farewell messages to their parents. They plead to be rescued. They didn’t want to die. They were scared.

In February 2021, the City of Ansan, where the Danwon High School is located, announced an international design competition for a memorial park and building. The competition brief identified three design objectives for the project: first, to create “a space of remembrance and respect for life,” where the memory of this tragic event is remembered through education programs and exhibitions; second, to create “a space for recognition and raising issues,” such as the poor judgement of the captain and the crew, the incompetencies of the rescue effort during the disaster, and the State authorities’ dismal response during and after the disaster that led to a national upheaval. The organizers of the competition wanted to make this project a forum to discuss the State’s responsibility “in face of social disasters.” The third design objective was to create “a space for mourning and commemoration.” As such that, “the memorial park shall go beyond the modern concept of seeing life and death as two separate things. Rather, it shall connect and remember death with present life.” (416 Memorial Park International Design Competition Design Guidelines, 2021)

To design an architectural proposal that tries to fulfill these three objectives is both an ambitious and emotional undertaking. My firm worked on this design competition in the midst of the Covid pandemic, as we were all scattered away from our studio and connecting only virtually. After reading more about the disaster and watching the online posts of the students, we decided to come back to the studio. The grief we felt was too deep to bear alone. As we were all feeling our own fragility in this seemingly foreign land created by the pandemic, we tried to “feel into” how it felt for those on the ship, where the balance first gradually and then, irrecoverably, was lost. It was this questioning that led us to the concept of our proposal: to create a space of negotiation between the tilt and the upright. By challenging the land-born understanding of our P-space, the design intent is to create a new L-space that can help us develop empathy with what it means to be in a place where the balance between buoyancy and gravity is forever lost.

The project creates an oblique volume that intersects the ground, shaping two major planes: the plane of tilt and the plane of balance. The tilted plane defines the floor of the building, as such it becomes the new ground plane. Whereas the horizontal plane, which relates to our land-born canonical position and represents what balance means to us, exists in the project as a juxtaposition of the plane of tilt to remind visitors that they are inside a new P-space. The tilt of the building causes it to sink into the ground plane on one end, which is defined by a reflecting pool, and on the other end it cantilevers over it. The enshrinement space is located below the reflecting pool.

The two planes intersect at the center of the Memorial, which is marked by a cylindrical space—the Hall of Harmony. (Figure 12) In this space, the datum line of balance is marked by a horizontal slit opening, which is connected to the reflecting pool outside. Water gently sips into the Hall of Harmony from the port side of the space, referencing the port side tilt of the ferry. The upright exists only in the center, and visitors explore moving toward the port side that is wet or the starboard side of the hall that is dry. As visitors swing inside this space, they experience the changing notions of the P-space—constructing for themselves the meaning of balance and its loss. They are reminded that the ground plane is not to be taken for granted.

Figure 12 - Hall of Harmony

As the building cantilevers out over the reflecting pool, the sloping plane of the exhibition hall visually connects through an upside-down oculus to the Enshrinement Space, located underneath the reflecting pool. The exhibition hall receives its light only from the reflected light beams that bounce off the pool. Visitors can feel the omnipresence of the Danwon High School students in this space, and they are reminded that the exhibited sneakers, sweaters, headphones that were salvaged from the ship are not mere everyday objects. They are extraordinary reminders of unfulfilled lives. There is a visceral connection between the physical objects that once belonged to the students and their omnipresence within the spaces. The upside-down oculus reverses the positive axis of our land-born P-space. [Below] becomes [above].

The premise of our design proposal for the memorial park and building is to create dissonance, by altering the P-space of the visitor, changing their canonical position, so that as they search for equilibrium, they will need to challenge the meaning of balance. From the perspective of educational psychology, cognitive dissonance is central to knowledge development. (Adcock, 2012, p.588).

According to Piaget, perturbation or conflict is “the most influential factor in acquiring new knowledge structures.” (Piaget, 1985, p.33) In fact, he argues, it is only through continuous equilibration of disequilibria that we develop better cognitive constructs. The cylindrical space of the Hall of Harmony, the oblique plane of the museum, and the upside-down oculus are all spatial constructs that challenge the established norms of our canonical position, and hence demand the visitor to create a new L-space, a new meaning of balance. The dissonance in space requires the visitor to continuously search for equilibrium, and thereby, as Piaget argued, allows the development of better cognitive constructs. In this process, the emotional empathy that develops out of our grief deepens into taking cognitive perspectives toward loss, remembrance, and our collective responsibilities in the face of social disasters.

Summary: The Geometry of Empathy

The interdisciplinary connections amongst discourses of spatial cognition, language acquisition, and development theory create an important basis to theorize the transformative potentials between perspectival projections in the physical (architectural) environment and perspective-taking in psychology. Based on these interdisciplinary readings, this essay discussed how the physical environment can influence the development of perspective-taking, and more specifically, how the purposeful design of spatial constructs can nudge us toward being more empathic.

Deixis is the most obvious way language and context relate to each other. (Levinson, 1983) The decision to explore design concepts based on deixis and empathy sprung from Herbert Clark’s argument that our perceptual space (P-space) influences our language space (L-space). (Clark 1973) His theory that the properties in P-space can also be found in the properties of L-space led me to the premise that if we can alter the perceptual space purposefully, we can potentially create new narratives, ones that can encourage us to be more empathic.

Geometry is a common ground that deixis and architecture share. The concepts of projective geometry are not merely rules of representation, but a set of forces that are omnipresent in our imagination and spatial perception, and consequently instrumental in the development of social and spatial cognition.

Transporting perspective taking in empathy from psychology to the perspectival (architectural) space, through the use of projective geometry, is the intellectual hinge of this essay. It is my argument that the forces that operate in our spatial cognition also have the ability to shift perspectives and therefore help us develop empathy. This is what I call the geometry of empathy.

References

416 Memorial Park International Design Competition Design Guideline (2021).

Adcock, A. (2012) Cognitive Dissonance in the Learning Processes. In Encyclopedia for the Sciences of Learning. Springer Press.

Clark, E., & Sengul, C. (1978). Strategies in the acquisition of deixis. Journal of Child Language, 5(3), 457–475.

Clark, H. H. (1973). Space, time, semantics, and the child. In T. Moore (Ed.), Cognitive Development and the Acquisition of Language (pp. 27–63). Academic Press.

Denis, M. (2018). Space and Spatial Cognition: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Routledge.

Evans, R. (1995). The Projective Cast: Architecture and Its Three Geometries. MIT Press.

Festinger, L. (1957) A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Fillmore, C. (1997) Lectures on Deixis. Stanford University.

Foucault, M. (1994). The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Routledge.

Levinson, S. C. (1983). Pragmatics. Cambridge University Press.

Mooney, C. G. (2013). Theories of Childhood, Second edition: An Introduction to Dewey, Montessori, Erikson, Piaget & Vygotsky. Redleaf Press.

Piaget, J. (1971) The Child’s Conception of the World. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Piaget, J. (1985) The Equilibration of Cognitive Structures: The Central Problem of Intellectual Development. Translated by Terrance Brown & Kishore Julian Thampy. University of Chicago Press.

Noir, T. (n.d.) Berlin Wall – Thierry Noir. https://thierrynoir.com/biography/essays/berlin-wall/

Proulx, M. J., Todorov, O. S., Aiken, A. E., & De Sousa, A. A. (2016). Where am I? Who am I? The Relation Between Spatial Cognition, Social Cognition and Individual Differences in the Built Environment. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00064

Thaler, R., & Sunstein, C. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth and Happiness. Penguin Books.

Tversky, B. (1996) Spatial Perspective in Descriptions. In Bloom, Peterson, Nadel, and Garrett (Eds.), Language and Space. MIT Press.

Wood, D. (1998). How Children Think and Learn (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishing.