Inverting the Deictic Center, and Empathy through Awareness

June 05, 2025

By Aybars Asci

The deictic center locates the first person at the center of the construct, making it an inherently egocentric frame of reference. In both design strategies discussed to counter this egocentric bias—the visual echo and the visual counterpoint—the concept of juxtaposition plays a key role in perspective taking and helps us move toward a deeper understanding of people, time, and space, consequently allowing a more empathic environment. For instance, in the three niches conjecture, the first, second, and third person are juxtaposed on the same deictic axis, encouraging us to see the point of view of the other. On the other hand, the visual counterpoint discussed for the Lima Museum project allows us to relate through different layers of historical contexts within the same space.

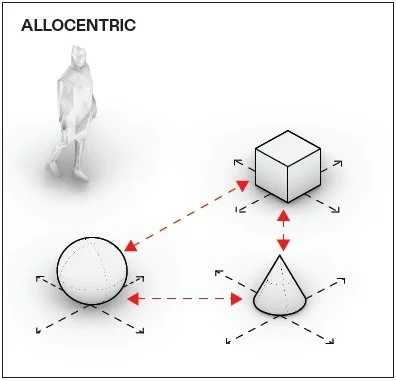

Figure 1 Comparison of the three spatial frames of reference. Isocentric frame of reference, added to the egocentric and allocentric frames of reference as a new way to conceptualize pluralistic narratives.

What if we invert the deictic center, and instead of putting the first person at the center of the construct, we put the object at the center, and thus allowing the nonhuman object to construct its own narratives? This conceptual shift will create a third spatial frame of reference, different from the egocentric and allocentric frames of references, both of which are based on human-centric points of view and carry the contextual bias of the time and place in which the narrative is constructed. By contrast, a spatial frame of reference that locates a non-human object as the anchor gives an autonomy to the object, allowing it to construct its own narratives. I call this concept an “isocentric frame of reference.” The object in an isocentric frame of reference has the agency to construct its own deictic center through projections toward the first person’s deictic center. (Figure 1, right) The potential to construct different juxtapositions within each of these projections will allow us to build multiple narratives for the same object, deepening our understanding of it.

The next project creates a device that constructs an isocentric frame of reference for a historical artifact, allowing us to build both emotional and cognitive empathy toward the socio-political circumstances and consequences of the time the object was constructed and, subsequently, subverted. Furthermore, the juxtapositions within the spatial construct allow us to deepen our understanding of ongoing conflicts and their respective consequences to society and the environment.

Figure 2 Segment of Berlin Wall behind a picket fence in Kowsky Plaza

Kowsky Plaza, located along the Battery Park City Esplanade in New York, is a small pocket park that contains a seemingly circumstantial assemblage of public attractions such as a dog park, a children’s playground, a volleyball court, New York City Police Memorial, and a segment of the Berlin wall. The Berlin Wall segment was given to the Battery Park City Authority in 2004 by the German Consulate, and today sits on the Eastern Edge of the park, uncomfortably close to an apartment building, paradoxically surrounded by a metal picket fence. Most park visitors stroll past it without even recognizing it.

Concerned about the deterioration of the mural on the wall segment due to its decades-long exposure to varying weather conditions, the Battery Park City Authority issued a request for proposals from architects to design a protective envelope in 2022. The pragmatic concern of paint deterioration and the discussions to find solutions for preservation inadvertently brings us into deeper questions of what this object represents, how we should preserve it, what kind of relationship should we have with it and what kind of relationship should it have with us, and notwithstanding, how it should sit at the eastern corner of Kowsky Plaza.

The Berlin Wall, the most recognizable symbol of the Cold War, was, of course, more than a wall; it was a series of walls, fences, a vehicle ditch, traps, observation towers, and a zone ominously named the “death strip,” separating East and West Berlin. The segment of the wall that sits at Kowsky Plaza was originally located along the Kreuzberg neighborhood in Berlin, and the mural on the wall was painted by the French artist Thierry Noir in 1984. Noir’s abstract minimalistic outlines with few colors grew out of the pragmatic realities of finishing the painting quickly without being caught by East German border guards. When Noir started painting the murals, at first, the West Berliners were suspicious; they took it as some sort of propaganda activity, but later embraced the murals. He was joined by other artists. For Noir, this act of defiance was a subversion of a war barrier into a humanistic canvas. As he stated, the act of painting the murals made him stronger than the wall itself.[1]

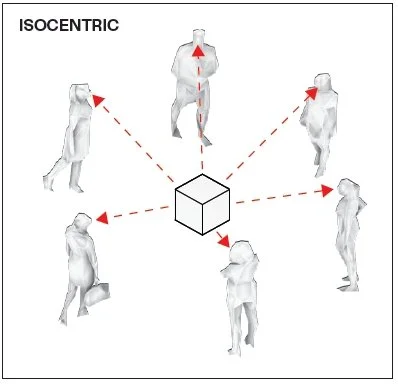

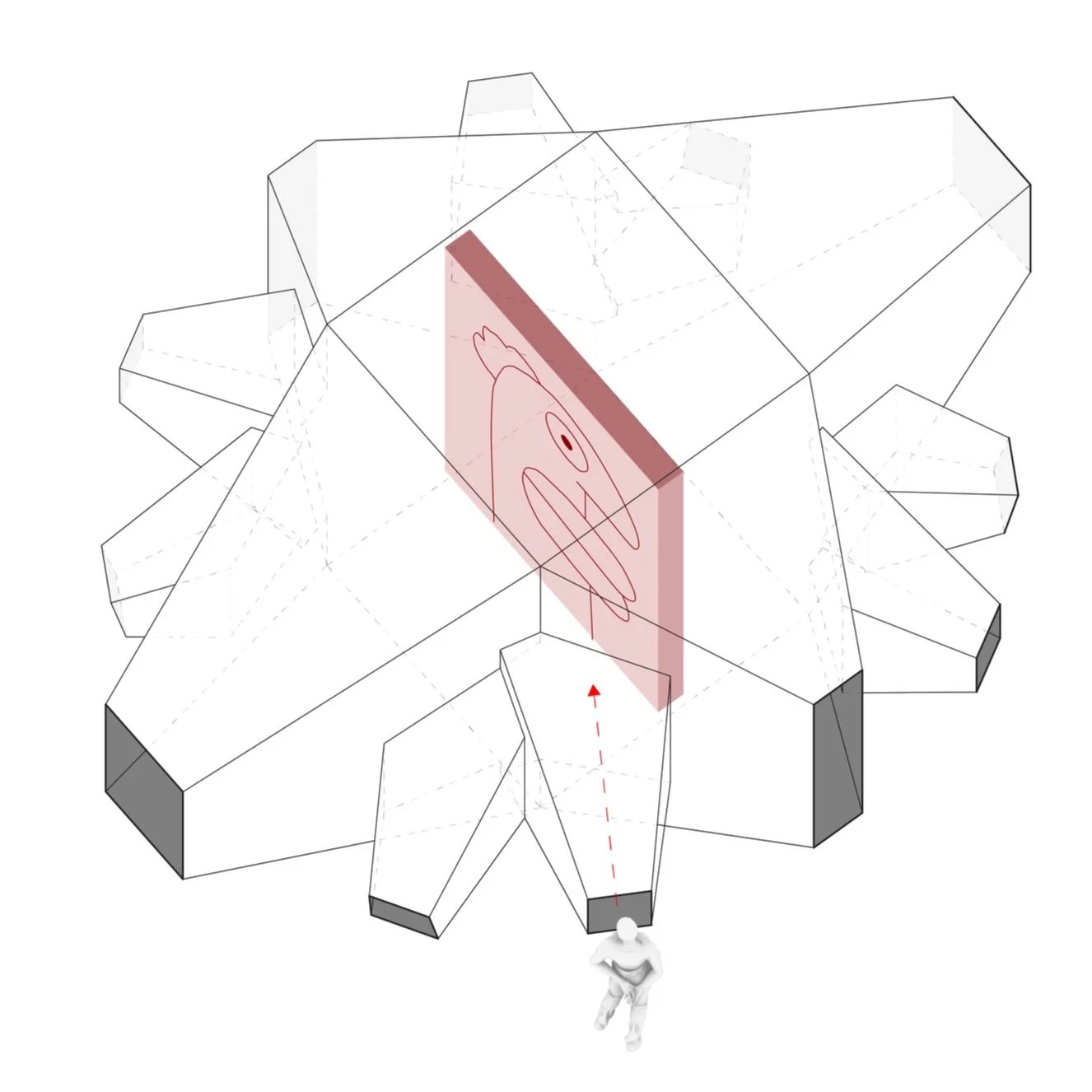

Figure 3 Two different schemes of the isocentric frame of reference. The Berlin Wall fragment is located at the center illustrated with the red rectangle.

But what does his act of defiance, this subversive transformation of a Cold War apparatus into a humanistic artifact mean today, when a piece of it sits at the corner of a pocket park in Manhattan surrounded by a picket fence? In its new context, is it reduced to just a memento, a souvenir brought to New York City from another time and place?

As my office contemplated the Battery Park City Authority’s requirement to create a shelter for this segment of Berlin Wall, we asked ourselves how we can redefine the dual narratives of humanity—oppressive and liberating—represented by the canvas and its painting. How could we reterritorialize this complicated piece of history in its new context and give it a voice that elevates it from an object of consumption as in a souvenir; transforming it into something that can bring us a heightened awareness of socio-political events of past and present? Our design proposal constructs an apparatus that locates the segment of the wall within an isocentric frame of reference. We designed two versions of the same concept. The first one is based on pure radial projections. The other option recognizes the cardinal axes of the wall and introduces the radial projections inserted in between them. (Figure 3) Both are manifestations of the same concept, even though they have different formal expressions.

Figure 4 Plane A shown in the diagram is located at each deictic axis and the juxtaposed stories are placed on these planes.

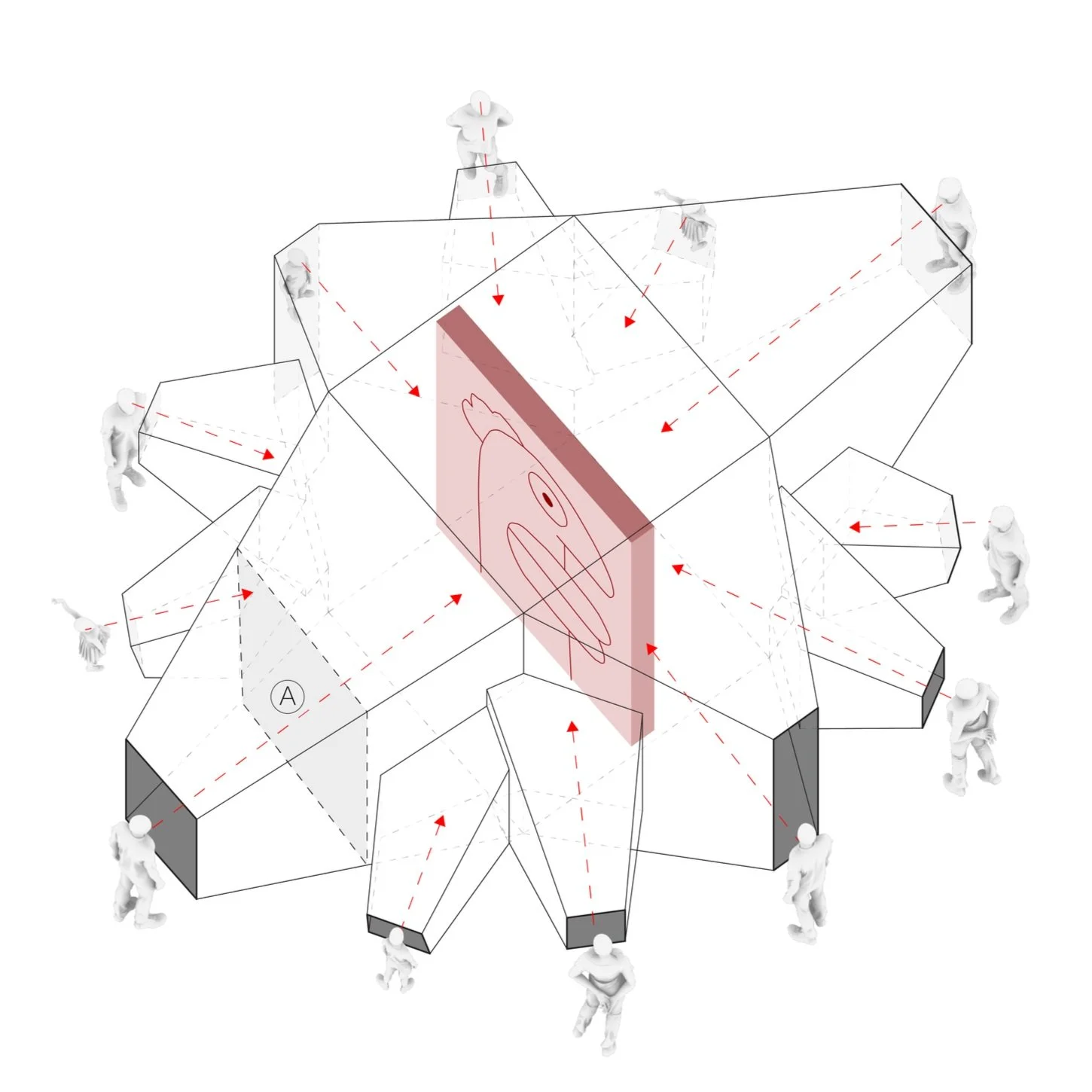

Figure 5 Isocentric frames of reference, multiple narratives juxtaposed on each deictic center.

In both schemes, the individual deictic centers for each person looking to the wall sees a framed view of the mural. The carefully curated perspectives toward the wall are in fact part of the isocentric projections of the wall, constructing its own narratives. Along each deictic axis, a frame is constructed to juxtapose on other narratives. The new narratives on these frames are intended to be temporary exhibits that will be curated by other artists that reflect their own conceptualization of the wall. (Figure 4, Plane A) In other words, they will be layering over Noir’s painting, creating yet another form of subversion of the wall.

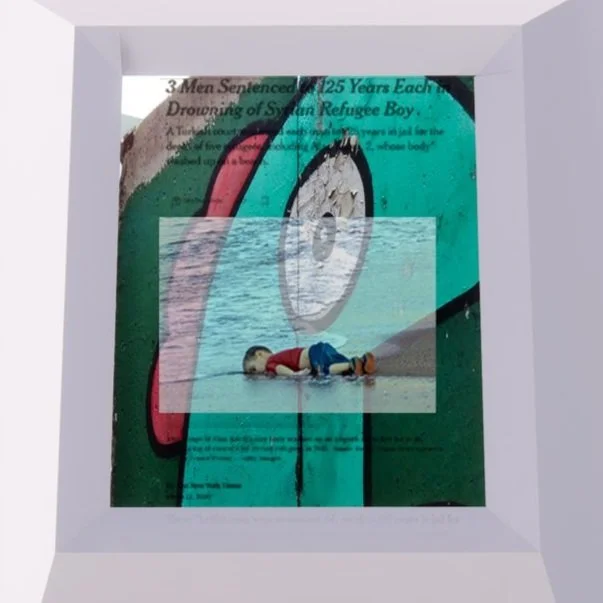

Figure 6 Berlin Wall in isocentric frame of reference. The image on the left shows the juxtaposition between the mural on the wall and the image located at the deictic axis.

To illustrate how juxtapositions work at the isocentric frame of reference, we have curated one story line. Figure 6 shows one of the perspectives of the wall juxtaposed by the image and story of the Syrian refugees trying to cross the Aegean Sea on makeshift boats in 2015. In this particular image, we see a little boy who tragically drowned and washed out to the beach. The eye of the mural is looking toward us as we look back at it. And there is the little boy, lying motionless on our deictic axis. In this juxtaposition, Noir’s drawing of the big eye is looking at the little boy, witnessing another human tragedy, on another death strip—in this case an Ancient Sea transformed into one.

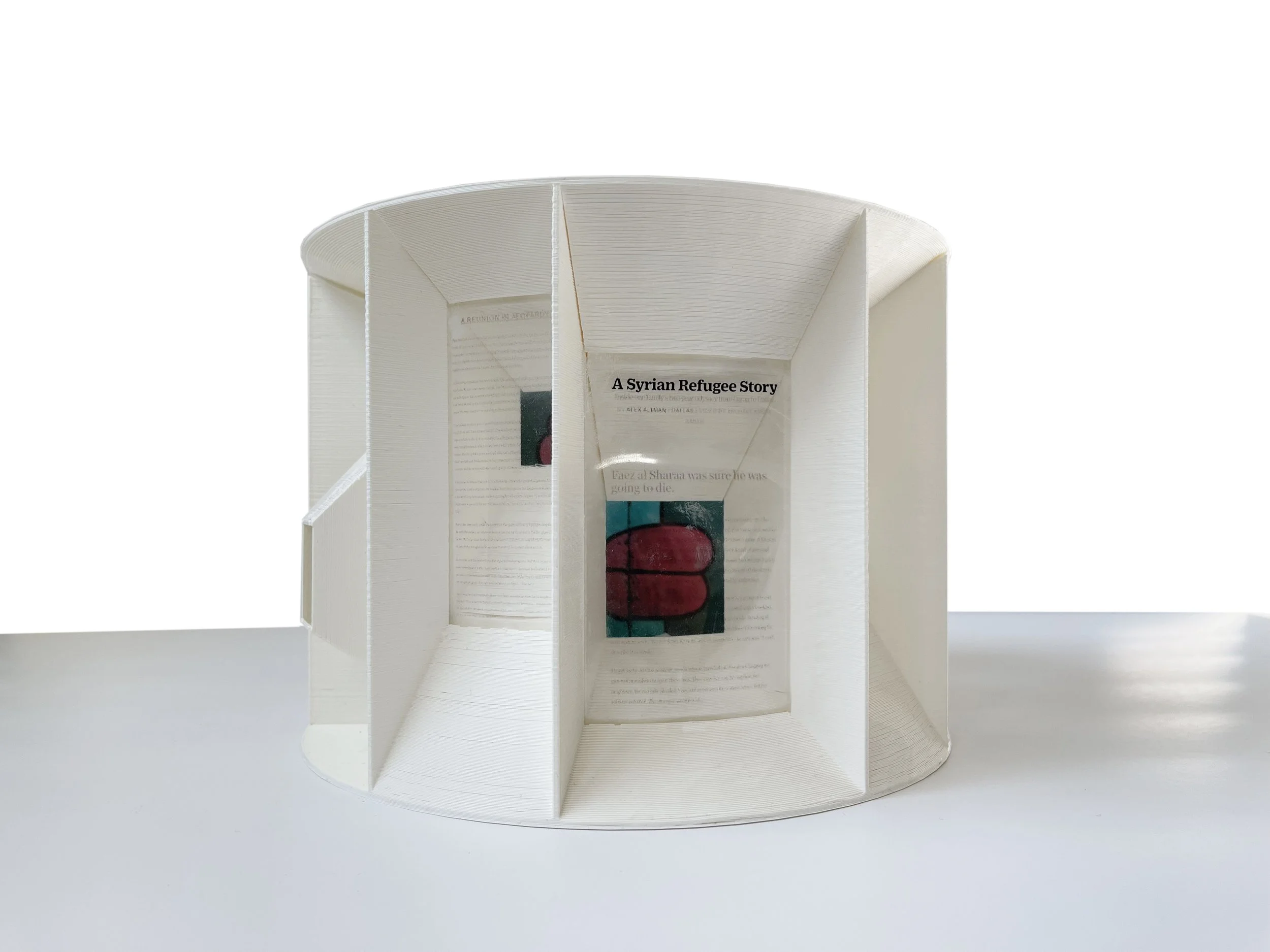

Figure 7 Photographs of the physical model.

In Figure 7 (bottom) we can see another juxtaposition: the lips of the mural framed over a news story of the tragedy. In this narrative, the bright red lips are motionless. The person reading this is reminded of the importance of her own voice. The mural reminds us that we have a responsibility to speak up and to act against atrocities. The person looking at these juxtapositions is encouraged to think of this segment of Berlin Wall not as a relic from the past, but as a reminder that human tragedies continue to unfold and peaceful coexistence of societies is contingent on fragile balances. These balances depend on perpetual emotional and cognitive empathy for each other, as much as they depend on international treatises and protocols.

Reference:

[1] Thierry Noir, “The Berlin Wall,” https://thierrynoir.com/biography/essays/berlin-wall/